A post-money valuation is what a company is believed to be worth after raising a priced round of equity financing.

An essential part of leading a startup from formation to exit is raising capital, and when it’s time to raise a round of equity financing from investors, a startup valuation becomes necessary. The term valuation encompasses two distinct types: pre-money and post-money. This article focuses on post-money valuations with insights from John Rikhtegar, RBCx’s VP, Growth Capital. John supports early-stage clients across capital fundraising and strategic growth, and leads direct, indirect, and strategic investment opportunities. Read on to learn the basics on post-money valuations, including:

- What is a post-money valuation?

- How a post-money valuation is calculated

- How post-money valuations impact financing rounds

- Methods to determine a startup valuation

What is a post-money valuation?

A post-money valuation is the projected value of the company after raising a priced round of equity financing. Conversely, a pre-money valuation is what a company is believed to be worth prior to completing a financing round.

A valuation, essentially, is the perceived value of a company as determined by the company, its investors, prospective investors, and external market players (such as market analysts). For the company and its investors, the valuation establishes the worth of the startup at a specific point in time, and distinguishing whether it’s a post-money or pre-money is important.

How do you calculate post-money valuation?

The post-money valuation is calculated as the pre-money valuation plus the additional capital raised during the priced round of equity financing.

A primary function of post-money valuations is to determine the percentage of the company an investor is purchasing in a financing round. Once the post-money valuation is established, an investor can divide the investment by the post-money to calculate the just-purchased ownership stake in the company.

Post-money valuation example

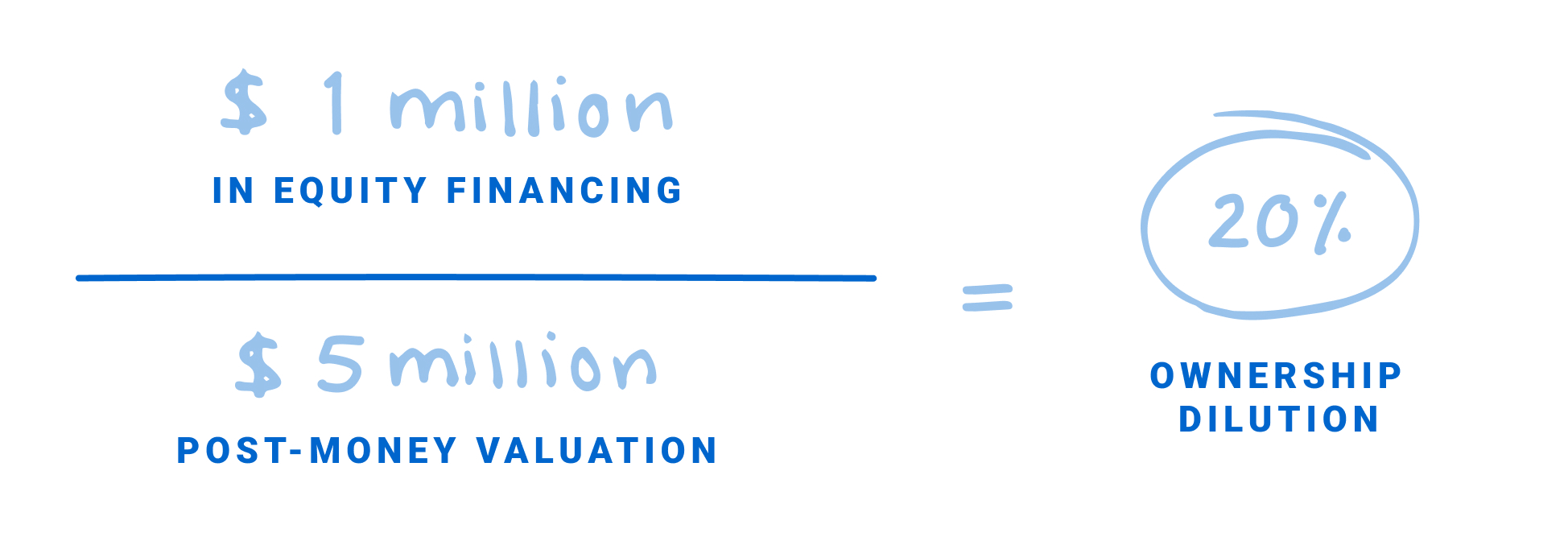

Founder, Anika, owns 100 per cent of her business. She is looking to raise pre-seed capital for her startup and plans to raise $1 million on a $4 million pre-money valuation. This would imply a post-money valuation of $5 million ($1 million + $4 million = $5 million).

To determine how much equity Anika would be giving up for the $1 million in equity financing, divide the $1 million by the post-money valuation of $5 million, which equals 20% ownership dilution.

How post-money valuations impact financing rounds

Scaling private companies often go through multiple financing rounds as they progress through the typical startup stages. And, as more capital is raised on subsequent financing rounds, managing ownership dilution is a key area of focus for existing investors.

In exchange for their capital, new investors are typically granted preferred (“Pref”) shares. Preferred shares form the basis of an investor’s shareholder equity post investment and include benefits over the common shares typically held by founders, employees, and few potential early-stage investors.

“A company goes through a ‘down round’ if the pre-money valuation is lower than the post-money valuation of the previous financing round.”

“Preferred shares are typically provided to safeguard against overvaluation,” says John, and include a liquidation preference (typically 1.0x), participation right, and anti-dilution rights. These benefits help mitigate investors’ risk.

If a company’s pre-money valuation is higher than the post-money valuation of the previous financing round, the company is said to go through an ‘up round’. Conversely, a company goes through a ‘down round’ if the pre-money valuation is lower than the post-money valuation of the previous financing round.

Implications of a down round for startups

As private companies seek startup funding, down rounds have historically been avoided at all costs. They can have adverse follow-on implications for the company, its employees, and the underlying investors involved, such as:

- Financing attractiveness: Attracting new investors to current and future rounds of financing may be difficult if the company has a track record of not being able to meet investor expectations and business milestones.

- Talent retention: Shares issued at a lower price may leave current employees with significantly less upside in their stock option packages or potentially ‘out of the money’, which occurs when the most recent share price is lower than their option strike price (the price at which the owner of the option can exercise their right to buy the stock). Ensuring that employees are motivated and financially incentivized is key when managing a down round financing, which will most likely require a restructuring and re-pricing of employee stock options.

- Investor-friendly terms: When a company is in dire need of capital and lacks financing alternatives, leverage remains in the hands of investors. When structuring a financing round, leverage can be seen in the form of investor-friendly terms, which may include an above 1.0x liquidation preference, seniority structures, participation rights, or investor put rights. These ‘structured’ terms, however, may favour new investors and damage the ownership and subsequent payout for existing investors and all common equity shareholders, including employees.

- Public perception: Taking a down round has historically been viewed as a major warning to the public (in instances where they become aware), and could damage a company’s public perception, impacting both internal company morale and overall business performance.

“The trajectory for private company building should not always be expected to be ‘up and to the right’, and seeing valuations move in both directions should therefore be anticipated.”

It’s important to note that although down rounds have historically held these adverse implications for the various company stakeholders involved, founders who have the option to either take a down round, or keep valuation flat by incorporating structured terms, should strongly consider the former. “The trajectory for private company building should not always be expected to be ‘up and to the right’, and seeing valuations move in both directions should therefore be anticipated,” says John. “This is exactly in line with what we all witness in the public markets, with valuations being adjusted in real-time in both directions.”

Methods to determine startup valuations

Determining a valuation can be relatively straightforward for late stage, established companies because they have matured operating and financial data as well as various public market comparables to benchmark against. For high growth, early stage startups that are pre-revenue, the endeavour can be more challenging since these companies lack the same level of operating history and financial data of their late stage peers. As a result, the valuation process at the early stage of a startup is frequently referred to as more of an art than pure science.

“An early stage startup valuation will be based on a more qualitative set of investment heuristics, such as the composition and background of the founding team, the concentration and expected growth of the market, the business model and projected funding needs, target business milestones, and other comparable recent early stage transactions,“ says John.

A late-stage, mature startup with more extensive data from company operations, however, will be analyzed through a more rigorous quantitative and qualitative assessment.

“For mid-to-late stage companies, sample quantitative heuristics—both historical and forecasted—used to assess an appropriate company valuation may include revenue growth rates, net new ARR (annual recurring revenue) added per quarter, average revenue per customer, cash conversion rate, burn multiple, net revenue retention or churn rates, and other operating metrics such as sales cycle length, customer onboarding length, and sales and marketing efficiency,” says John.

Two common methods used for later stage valuations are discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis and multiple analysis.

The DCF analysis is based on the future cash flows of a company, which is then discounted back to the present-day value to build an implicit net present value (NPV). An investor can then use the NPV as a starting point to price an asset and align their target return expectations with a fair company valuation.

The multiple or comparable analysis allows investors to benchmark a company to other private and public holdings to determine whether its perceived valuation is justified against peers.

Valuations are subject to change

A valuation is subject to change as the company scales. While the valuation of a publicly traded company is updated in real-time, private market valuations are not updated as often and therefore may not reflect its true current business value.

“A company that raised capital two years ago at a $100 million valuation may still hold that valuation today simply because they have not undergone an independent valuation process since, nor completed a subsequent priced equity round. The valuation, therefore, does not reflect the current company’s state,” says John. “It may have grown significantly and be worth much more than $100 million or, conversely, it may have experienced little growth and worth much less. This makes private market benchmarking and venture capital portfolio evaluation a very interesting process.”

Who determines the valuation of a startup?

Both the buyer (investor) and seller (founder) agree upon the valuation for a business. It’s typically one lead investor that takes the lead on negotiations with the company to determine the terms and valuation of the investment, identify and recruit other investors to participate in the round, and close the deal.

“Though all investors, to some degree, will perform their own due diligence and valuation analysis on the company, the lead investor is ultimately the one that sets the price, or valuation, of the company for investors to pile in on,” says John.

The post-money valuation of a startup is necessary for investors to determine their ownership stake in the company in a financing round. For founders seeking out venture capital, understanding the valuation process is instrumental to the ongoing success of their startup.

RBCx backs some of Canada’s most daring tech companies and idea generators, turning our experience, networks, and capital into your competitive advantage to help drive lasting change. Speak with a RBCx Technology Advisor to learn more about how we can help your business grow.